BY Martha Roskowski, TFN’s Mobility and Access Collaborative

I am a fan of study tours. There is magic in immersing a group of leaders in a place, watching them learn about policies and approaches, then helping them sort through what is most relevant to their situation and bring the ideas back home.

In recent years, I helped lead groups of funders studying mode shift, electrification and congestion pricing in London, Amsterdam and Stockholm. While at PeopleForBikes, I helped shepherd more than 300 elected officials, city staff, advocates, funders and community leaders on tours in the Netherlands and Denmark.

Lured by stories of a rapid rise in people riding bikes in Paris, I visited in fall 2023 to evaluate the lessons the city might teach U.S. leaders. My transportation geek friends are abuzz about the numbers. LeMonde newspaper reported that bicycling in Paris doubled between October 2022 and a year later. The city’s own report from 2021 to 2022 found an impressive 3% growth in bike facilities, 18.9% growth in bike use, 2.5% reduction in car travel and 16% fewer fatal crashes.

I recruited a study tour expert to join me on the exploration. Dr. Meredith Glaser of the Urban Cycling Institute wrote her PhD thesis on reshaping urban transport policy. Along with Lauren Ghidotti, an Urban Cycling Institute intern, we rode bikes, talked with local leaders and discussed our observations. We joined the rush hour crowd of locals biking to work or school, whizzing past car traffic. My unofficial counts found nearly as many women riding as men and two-thirds of riders without helmets, both indicators of perceived safety.

Paris is not like most U.S. cities. It is very dense, with 56,000 people per square mile, more than twice NYC’s 27,000 per square mile. The street network was established before the automobile. They didn’t bisect the center of their city with interstate highways. A robust transit system and a culture of walking mean many within the city live car-free. Many of the drivers angry about the transformation live in the suburbs so do not vote in Paris elections. And yet, many lessons from Paris are transferable to the US context, including:

- Elect a visionary mayor who can maneuver through complex governance: I posit that a courageous mayor is the single most important factor in a city making significant progress on biking. In France, Mayors hold unilateral administrative and executive power, with a 6-year mandate. Mayor Anne Hidalgo campaigned for re-election on a promise to complete the bike network. She won in 2020 with 20% more votes than her nearest challenger. She strategically appointed smart (and female) transport directors who embraced her vision. Most U.S. cities have plans on the shelf and committed staff who just await the political charge to get the designs on the ground.

- Have an ambitious plan: Following the re-election of Mayor Hidalgo, the city rolled out Plan Velo: Act 2, an updated plan promising 350 km of new bike lanes and 300 school streets by 2026. In 2019, a Collectif of organizations, agencies and individuals proposed an ambitious bike network for the broader Paris region. The plan, Réseau Vélo Île-de-France, has been embraced by the regional government with commitments of €500 million to help build out 750 km of express cycle routes.

- Embrace opportunity: As host of the 2024 Summer Olympics, meeting the mobility needs of 15M visitors in a city of just over 2M residents included accelerating bike plan implementation. Every U.S. city planning for major events (hello, Los Angeles) could look to Paris for lessons on rapid response to new demands. When the city went into lockdown for COVID-19, staff raced to retrofit streets to prepare for socially distanced travel in a city heavily reliant on the Métro. As the end of lockdown approached, city leaders chose to limit private vehicles on Rue de Rivoli, making it the premiere east-west bike corridor through the heart of the city. Frequent transit strikes inspire people to adopt more reliable and individual transport options.

- Embed biking in a broader vision: Plans for biking live within a comprehensive transportation system of walking, buses, subways, trains and vehicles. Biking supports broader plans to improve air quality, build the 15-minute city and expand social housing. Paris’s robust climate action plan promises to plant 100,000 trees, install more solar, retrofit buildings and clean up the water of the Seine.

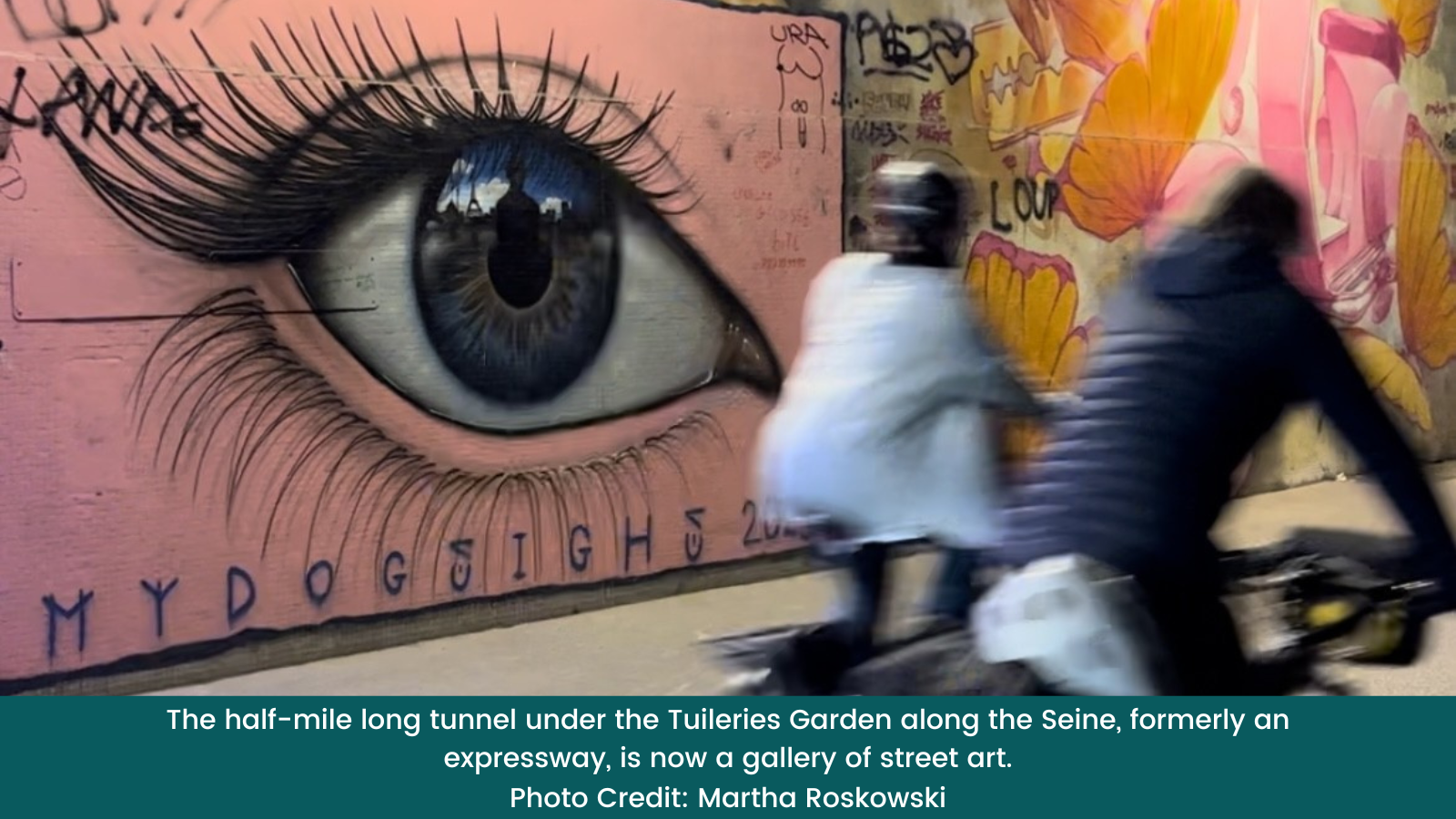

- Show rather than ask: In 2014, cars were banned from the Left Bank of the Seine River. Short summertime closures of the expressway on the Right Bank became a 6-month pilot in 2016. The resulting popularity and leadership by the city led to the permanent closure of both banks in 2017. Despite protests from suburban drivers and concerns of gridlock (spoiler: didn’t happen) the banks of the Seine are now a linear celebration of biking, walking, beaches, music and public life. The short-term pilots built public support for the bigger moves.

- Build a bike culture through education and partnerships: We got the impression that agencies work more closely with non-profits than in the U.S. The City of Paris supports associations that help immigrant women learn to ride bikes and provides free office space to the grassroots group MDB in return for providing cycling information. The Collectif includes regional governments that fund the organization that advocates for better biking. As advocacy groups in the U.S. rely on foundations, events and membership for funding, adding a dose of public funding is worth exploring.

- Aim for good enough: Paris’s network lacks the connectivity of Dutch cities where every road provides comfortable facilities for bikes. But the network in Paris is safe enough, connected enough and convenient enough that it passes the simple test – people are using it. One local described the system as “like jazz, with lots of improv.” Protected one-way and two-way bike lanes might shift to a few blocks of older painted lanes or shared pathways in the center of boulevards. Facilities sometimes end at the big plazas and then pick back up on the other side. It worked for me, a cautious rider, as long as I followed the green lines on the map. Traffic moves slowly and there are enough bikes that drivers expect us.

- Delight in the details: The bureau in charge of architectural consistency decreed that granite blocks would be used as bike facility separators. They are far more pleasing and durable (albeit expensive) than our ubiquitous plastic posts. The signs and signals engineers are figuring out how to move bikers, pedestrians and drivers with consistency. At a complex five-way intersection near Pere-Lachaise cemetery, I sat at a sidewalk cafe and counted 29 newly installed concrete bulb-outs, diverters and refuge islands that guide bikers.

- Bikeshare can work: In 2022, 25% of trips by bike in Paris were made on the Velíb bikeshare system. I found it to be generally reliable despite spotty maintenance. With 19,000 bikes at 1464 stations, a bike is usually nearby. The one time I couldn’t find a usable bike within a few blocks, I just trotted to a nearby Métro station. I preferred the e-bikes, which make up about 40% of the fleet, so I could start quickly at intersections, keep up with traffic and climb the occasional hill without sweating.

- Remove parking and improve the walking experience: Paris is a parking reformer’s dream. The city is removing 70,000 on-street parking spaces —about half of the supply — to make space for two things: bikes and trees. While earlier designs painted bike lanes on sidewalks, more recent iterations are using space previously devoted to cars for bike infrastructure, returning sidewalks to people walking and streetside cafes. During our visit in October 2023, Paris had just started charging motorcycles to park on city streets, and in March 2025, voters approved a measure to triple the parking fees for large SUVs.

While there are many lessons from Paris, their work on including diversity, equity and inclusion in transportation planning seems less intentional than ours. On past European tours, delegates grilled local leaders on how they prioritize and measure social equity and racial justice in transportation planning. The answers usually left U.S. delegates unsatisfied. Our conversations in Paris were no different. To better understand the dynamics around immigration, racism, poverty, underrepresentation and civil unrest in France, we’ll need to reach beyond the transportation field to find experts, including academics and those with lived experience, who can tell the stories.

Meredith, Lauren and I concluded that study tours of biking in Paris would be valuable for U.S. leaders. A cadre of agency staff, advocates, community leaders and consultants are ready to tell the story. With careful route choice, we’d feel comfortable leading delegates around the city on bikes. The sheer joy of experiencing a city by bike is a powerful incentive to make change back home, but as Meredith notes, “Riding a bike on study tours is only one part of the experiential learning equation — what also matters is the quality of intentional conversations about change that lead to knowledge transfer. This means that beyond expert Paris-based speakers, we need skilled facilitators who can “broker” the dialogue and spur creative thought processes among the delegates.”

Our usual model is delegations of 10 to 20 leaders visiting for a week, with days split between learning from experts, experiencing the city by bike and talking among ourselves to digest the learnings and make plans for progress back home. The model works, but it’s labor intensive and the reach is limited. Meredith and I brainstormed new models that might scale better without overtaxing the limited time of our gracious local hosts. We’re happy to discuss tour possibilities with anyone interested. And if a visit to Paris isn’t feasible, the video library of Streetfilms is the next best thing.

I am also exploring a funder study tour looking at transportation and resilience in Japan in May of 2025 on behalf of TFN. If you’re interested in learning more, please reach out at martha@fundersnetwork.org.

About the Mobility and Access Collaborative

The Mobility Fund was conceived and is guided by the Mobility and Access Collaborative, an initiative of The Funders Network. The collaborative is working to reduce transportation related greenhouse gas emissions while eliminating the underlying historic and current inequities in the mobility system. The collaborative is led by a core group of regional, place-based and national volunteers who are shaping and guiding work on transportation, including funders from the Barr Foundation, The Bullitt Foundation, Energy Foundation, Jacob and Terese Hershey Foundation, TransitCenter, The George Gund Foundation, The Joyce Foundation and The Summit Foundation.

—

About the Author

Martha Roskowski is the program lead for the Mobility and Access Collaborative, an initiative of The Funders Network. She is the founder of Further Strategies, a consulting firm based on Boulder, Col.