Going PLACES: Generational Trauma Across Indigenous Communities

By Jonathan Cunningham, Program Officer, Seattle Foundation

Going PLACES is an occasional blog series featuring the voices and experiences of TFN’s PLACES Fellows. For more information on the fellowship, and to read past blog posts from our fellows, visit here.

Growing up and reading about the atrocities the United States government committed against Native American tribes in the past, those wounds always struck me as close in nature — related in a way — to the atrocities that enslaved Africans experienced during a similar time period in the U.S. Thus, I’ve always wanted to have closer relationships with Native Americans — to talk about our shared experiences. However, being raised in Detroit, Mich., didn’t allow for that. I didn’t know any Native American families as a child or young adult. So like many kids raised in a U.S. school system, I only knew what I read about in school or saw on T.V.

As a 2019 PLACES fellow, when the list of site visit locations was announced, I found myself most intrigued by visiting Bismarck, North Dakota. I was excited to learn we’d get a chance to spend time with Indigenous leaders on the ground in the heart of Indian Country to hear about what issues are most pertinent with the Lakota people. I was immediately excited, humbled and nervous to learn that we’d not only spend a day visiting the Standing Rock Reservation, but that we’d meet with members of their tribal council — a very rare honor. I first learned about the Standing Rock Reservation during the intense stand-off and fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016. The resiliency, resistance and indigenous wisdom which emerged during the protests at Standing Rock captured the world’s attention for 10 months. For anyone interested in learning more about it, check out videos and stories by Native filmmakers, who were best positioned to do the story justice. In January 2017, I wrote a story for City Arts Magazine in Seattle about one of the most powerful women I know, Tracy Rector, who is an Emmy-award winning mixed Choctaw/Seminole filmmaker, writer, storyteller, healer and executive director of the non-profit Indigenous Showcase, who traveled to Standing Rock with her son Solomon to experience the spiritual protest firsthand and capture it on film. Her account of the beauty she experienced at Standing Rock, juxtaposed with many of the problems and culture clashes that arose when larger groups of “white allies” arrived at the camp, is quite powerful. In a way, that’s a story which plays out time and time again in philanthropy as well.

I wrote that story just as my philanthropy career was beginning. My interview with Tracy Rector was published January 17, 2017. Ironically, that was also my official first day as a program officer at the Seattle Foundation. As a funder in Seattle, a city named after the Suquamish and Duwamish tribal leader Chief Sealth, it’s my responsibility to build alliances with the original inhabitants of this land, the traditional Coast Salish people. I have to humbly admit that my connections to Native communities as a funder are not as deep as I would like them to be. I have a long way to go in building stronger relations with the Native tribes in Greater Seattle. It’s not easy — but it’s not impossible either. At my most self-critical, I think it’s my fault for not trying hard enough or doing better outreach to ensure our grant programs have strong Native representation in the applicant pool. But I also have to remember many structural barriers exist that often prevent Native organizations from applying for grant programs, including one that doesn’t take much brain power to figure out: After 500 years, Native folks have ample reasons not to trust institutions. And despite the mutually expressed desire for Black folks and Native folks to work together more often, it doesn’t happen nearly enough. As a challenge to myself, I’d like to dive deeper into why that is.

Being in North Dakota opened my eyes to many things happening in tribal communities that I wasn’t previously privy to and I’d like to share those lessons with others. I found myself incredibly impressed during our site visit to the United Tribes Technical College, listening to Scott Davis who heads the North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission. Some of the things they’re working on building up is tourism, technology, clean energy, education, and strengthening relationships between tribal communities and the federal government. Davis, who is Lakota and Cheyenne, reminded us that most of the treaties signed by Native tribes and the federal government weren’t honored and were disregarded by local governments. The government’s legacy of giving their word and taking it back whenever they chose is a problem that’s centuries old and it still plays out today.

I immediately thought of the racist term “Indian Giver” used to categorize Native Americans who didn’t keep their word…who gave things and then took them back—and felt the irony. It’s takes an unfathomable amount of racism to commit centuries of atrocities against a people, craft treaties only to repeatedly break them and then label the Native Americans as the ones who were untrustworthy.

Other nuggets of wisdom that stayed with me: “Trauma is carried in our DNA. Alcoholism, boarding schools, child abuse. Mental health. A lack of access to health and wellness for our Urban Indians. Murdered Native women. These traumas are carried in our DNA. But my people also have resiliency and courage. They didn’t break us.”

There’s so much to unpack in that quote from Davis. I’m someone whose sobriety is incredibly important to me, thus my ears really perked up when Scott mentioned he was most proud of being 13 years sober. It’s no secret that alcoholism and substance abuse is a big issue within Native communities, just like it is within African American communities. That’s yet another thing where Black and Native folks have used substances as coping mechanisms to deal with the trauma that’s been inflicted upon us in this country for centuries.

Popular author, speaker and philanthropy professional Edgar Villanueva’s seminal book Decolonizing Wealth, also speaks about epigenetics and ways trauma is carried down through our DNA. Not surprisingly, Villanueva is Native American, thus this was another reminder of how the field of philanthropy would be wise to humble itself and learn from Native wisdom more often.

When Scott spoke about the murdered Native women, I couldn’t help but think of how this was becoming an epidemic all across Indian Country. According to Davis, part of the problem is jurisdiction issues between local/state officials and tribal police in investigating crimes. Tribal police fall under the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and there aren’t enough law officers to cover the vast territories on reservations. Scott mentioned there are times when there’s only one tribal police officer on and 911 response times can take upwards of 45 minutes. If this is the case, it’s not surprising crimes go unsolved.

Here in Seattle, our daily newspaper the Seattle Times, is running a powerful multi-part series video series about violence against Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). Roxanna White is featured in one of the videos. She’s an enrolled member of the Nez Perce tribe. I know her personally and her story of the sex trafficking that occurs within tribal communities is powerful and deserving of more attention. Seattle Foundation is now proudly partnering with Seattle Times on an Investigative Journalism Fund, and while there are many stories that deserve deep investigative reporting, having more resources committed to daylighting pertinent issues within Native communities is a worthwhile cause that we're looking at putting more muscle into as a foundation.

Through Davis we also learned that Native Americans weren't considered citizens until 1924. Before that they were considered wards of the government — on their own land. My jaw almost hit the floor. Peak racism at its finest.

The United Tribes Technical College offers 16 associate degrees, four bachelor’s degrees and a technical training program. Scott mentioned that within Native communities, they noticed that some of their youth were going to traditionally white colleges and experiencing culture shock. They were going to state colleges but unfortunately dropping out and coming back home. The need for a space like United Tribes Technical College reminds of how important Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are and how they have long served as a haven for Black students from the same cultural and racial issues indigenous students have been met with.

Lorraine Davis also spoke to us. She heads the Native American Development Center and helps with the Community Development Financial Institutions work. They offer peer to peer support for businesses. Peer support to help people in recovery. She was very knowledgeable in how Community Development Corporations (CDCs) work. She helps with streamlining the process to getting Native entrepreneurs business loans. She taught us about the website Prosperity Now and the invaluable data it provides when looking at trends within minority communities. They are working to get data broken down by tribes I’ve been using the website since I learned of it through her. Lorraine mentioned that there aren’t a lot of foundations in North Dakota but much of her work is supported by the Northwest Area Foundation.

One of her many one-liners. “If you’re looking for solutions, start with the tribes. They have resilience and solutions but people don’t ask.”

Lorraine, who is very strong in her personality, is Scott Davis’ wife but doesn’t like to be referred to only as that. She’s successful and has her own identity apart from her husband’s. Amen to that.

If I’m going to build the deeper relationships with the Native organizations whose work I’m responsible for funding, I’ve got a lot more work to do. I’ll continue to expand my outreach in Native communities, ensure there are Native community reviewers helping us making decisions for all of the grant programs that I manage, and learn the names of all the tribes in the Puget Sound area. That outreach can’t just be by email alone. You have to get out and spend time with some of the Native leaders in our community and let them get to know you. That’s the only way trust is built. One recent progress on this front is I’ve asked our Community Programs team to start each of our meetings with a Land Acknowledgement, and they agreed. If I’m doing all of these things "in a good way", as Standing Rock Tribal Chairman Mike Faith repeatedly said during our visit, I think I’ll make progress. It’s a responsibility that I, as a program officer, and foundations in general need to keep top of mind. Foundations based in the Puget Sound area undoubtedly owe a debt of gratitude to the Coast Salish tribes whose land we stand upon each day.

About The Author

Jonathan Cunningham is a program officer at the Seattle Foundation who brings a wealth of professional experience in developing, implementing and managing community initiatives. He is currently a Seattle Arts Commissioner with deep knowledge of navigating public, private and municipal partnerships. Jonathan previously worked at the Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP) as Manager of Youth Programs and Community Outreach efforts and is passionate about using arts & culture as a strategy to create racial justice. He is a graduate of the University of Michigan and founder of The Residency, a youth development through hip-hop program based in Seattle.

#CCLE2019 - We Shall Overcome: The Enduring Fight for Freedom and Justice

|

|

By Martha Cecilia Ovadia, Senior Program Associate, Equity and Communications

2019 Community Change Learning Exchange

December 4-6, 2019 | Montgomery, Alabama

What is the Community Change Learning Exchange?

The Community Change Learning Exchange (CCLE) aims to unlock and share knowledge and to create a safe space for funders to discuss past and current challenges in their community change work. The CCLE is intended to serve as a safe space for dialogue among funders that will allow them to discuss — openly — opportunities, challenges and perspectives in community change work. Ultimately, we aim to share some of these perspectives with the field of place-based philanthropy.

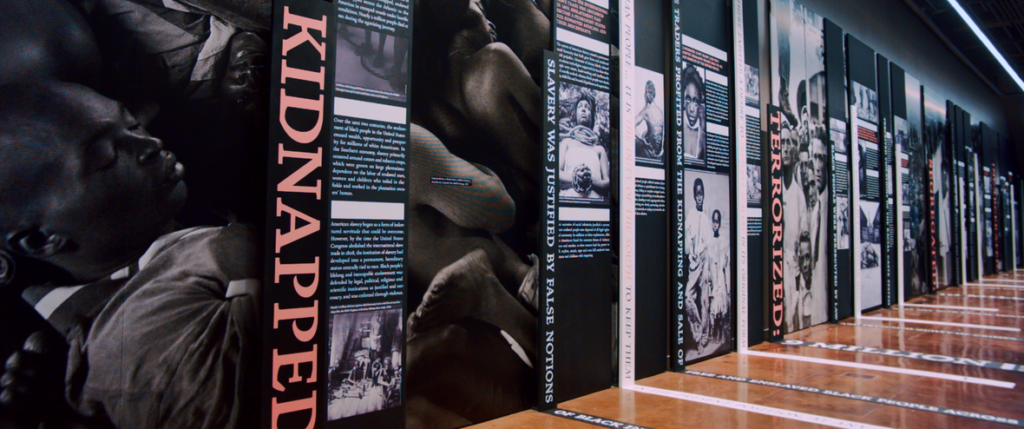

Our #CCLE 2019 theme this year is We Shall Overcome: The Enduring Fight for Freedom and Justice.

About CCLE 2019

CCLE Schedule

We will begin on the 4th with lunch, an afternoon tour of the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, understanding our history of oppression and a discussion on the implications of systemic racism, and injustice. We will learn about work being done to address these issues. This experience will be FREE for CCLE participants.

We will reconvene on the 5th with an opportunity to learn from people and place. In addition to peer to peer exchange, we will talk with local foundations, residents and community leaders about ways they are working to address issues impacting low income communities and/or communities of colors. We will discuss current challenges, opportunities and innovative solutions influenced by authentic community engagement. The day will conclude with a networking dinner with local funders and community leaders.

On the 6th, we will be led in a facilitated discussion to talk about funder practice and approaches, how we are complicit in upholding systems of oppression and offer advice to one another and the field on ways to advance our practice. We will conclude by 1 p.m.

Dress Code: Dress is casual; there will be some walking.

What are the desired outcomes of The Exchange?

• We hope that the occasional learning, sharing and challenging of one another through authentic conversations in a safe space will enable us to capture, cull and disseminate best practices to the field of place-based community change;

• glean learning opportunities from others to inform our own place-based community change work; and

• advance funder thinking and action on the importance and value of community change work in your own places.

Join us in Montgomery

Alabama is the site of many key events in the American Civil Rights Movement. Our host city of Montgomery offers an ideal setting to explore issues of race, equity and justice. This includes the Montgomery bus boycott, the violence against the Freedom Riders and the marches from Selma to Montgomery.

This city, the capital of Alabama, also represents an important place in the fight for voting rights. As we prepare for the upcoming elections and Census 2020, understanding this history and the complexity of this movement will enrich your experience and broaden your perspective.

Reserve Your Room for CCLE 2019

We invite you to reserve your hotel room now at the SpringHill Suites Montgomery Downtown for a reduced TFN rate of $159 per night. Reserve here.

About Community Change Learning Exchange (CCLE)

The Annie E. Casey Foundationconvened the first CCLE meeting in Baltimore in 2014 and has served as the CCLE convener and executive secretariat, but CCLE is not a Casey initiative. The foundations that hosted the CCLE meetings have been involved in place-based work, including implementing long-term community change initiatives (CCIs). The meeting explored lessons related to community engagement, race equity and inclusion, transparency, mitigating the effects of gentrification and displacement and other essential elements of effective place-based work. Community representatives also participated in CCLE site visits and discussions, allowing foundation representatives to engage with them at a depth that is unusual in many funder-grantee relationships.

CCLE is a vital forum for capturing and sharing knowledge, as well as a community of support for representatives of foundations engaged in placed-based community change. It offers a safe space for discussion and reflection that is hard to achieve when one is immersed in actually doing the work. CCLE augments the work of philanthropic affinity groups concerned with place-based work (all of which participated in CCLE) and provides a platform to inform the field about how to do this important work better. To date, approximately 100 foundation staff and other stakeholders participated in the four CCLE sessions.

Going PLACES: Rise Above

By Steven Higashide, TransitCenter

Going PLACES is an occasional blog series featuring the voices and experiences of TFN’s PLACES Fellows. For more information on the fellowship, and to read past blog posts from our fellows, visit here.

Our first order of business when we arrive in North Dakota for our most recent site visit as PLACES fellows, a red state and the 50th most travelled to state in the nation, was a conversation on assumptions:

What assumptions are you holding for this site visit as it relates to Bismarck?

What are your assumptions of Standing Rock Reservation? What are your expectations of the interactions and experiences that you will embark upon this week?

I didn’t know much about North Dakota outside of valleys, reservations, and of course the recent outcry at Standing Rock; a protest against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline or #NODAPL. This information, inferences to the current administration and my own knowledge of the history of indigenous oppression, meant my assumptions were filled with emotion — and not exactly the happy kind. There was excitement around learning about a new culture, but for the most part my assumptions centered around fear, anger, frustration, and anxiety for the indigenous people. How could it not, right? When I think about my own experiences in this country, with the history of marginalization and protests within the black community, I find it challenging to operate without a sense of anxiety in this climate. I assumed the people we would meet would operate in a similar space. Surprisingly, the most important lesson that I learned during this visit to Standing Rock was not about injustice — it centered around healing.

It is emotionally draining to operate in a space fueled by powerlessness, trauma, and hate. Those are not the items that we need to bring to the table in order to get to the work. We have to find ways to counteract our negative assumptions and emotions so that we can understand the pain that is being illustrated and learn how show up differently. I am reminded of this famous quote:

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” – Audre Lorde

How can we reframe our expectations to counteract the trauma and the responses that we are seeing? First, we have to be grounded. Can we drop everything that we thought we knew, and operate with a lens to understand?

The following takeaways from Bismarck were monumental for me in reframing my expectations and counteracting my own trauma responses:

1. Ask specific questions.

2. Try not to put your lens on the situation at hand.

3. Amplify the stories that are shared.

4. How do we actively check our privilege?

5. And in the immortal words of Kendrick Lamar: Be humble.

I found it was helpful to create this catchy phrase based on the key words in that list, plus Kendrick's reminder to be humble: Specificity, Lens, Amplify, Privilege — Kendrick Lamar S.L.A.P.s. (For those of you not versed on slang, music that "slaps" means music that's cool.) And Kendrick Lamar's music is banging, right?

I found it both encouraging and enlightening that the people of Standing Rock focused on prayer instead of fear. The Sioux Tribe have a spiritual connection to the land that dates back centuries. Their fight is about protecting this space that has provided sustenance at a very human level for years and years. More than land rights, civil rights, human rights, or access, the #NODAPL movement was about giving life—bringing and sustaining life. And it is important to the cause to be able to share that story and to control the narrative.

Tribe members told us that each morning they began #NODAPL with a prayer. Prayer was then taken aflame as campsites were started in other places and in communities across the world. Others began to join the protests seeing it through the indigenous lens. In addition, the Sioux tribe created an emergency preparedness team, filed lawsuits, and continued to test and monitor the construction of the pipeline. While the protest may be over, the fight continues.

The struggle has not been without negative lasting effects. The Sioux Tribe shared that they are dealing with issues of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The smell of tear gas and the sound of barking dogs is traumatizing. And to add further injustice, recent legislation has now made it a felony to protest a pipeline according to state law SB189.

What my time in North Dakota taught me is that if we are to do the work of justice and liberation, we must come from a place of grounding. This is not a simple fight. We not only need embrace the work, but we must fully embody it. In order to do those things, we have to make space for healing. It is, to me, the most important step of it all.

Our friends at Standing Rock did this through prayer, but there are many other methods to getting to this space: telling stories, creating safe spaces, centering the voices of the community are all measures that philanthropy can take to support communities that experience trauma and systematic oppression. We must understand, however, that it is not a short-term process, neither is it simple or easy. And so support for this work has to be just as resilient and just as responsive in order to create a dynamic shift.

As we have learned from Standing Rock, every case may not be a complete victory. But even in those times, our presence matters.

So, we have to presence ourselves in the movement. Ask yourself:

“What am I called to do in this work? What do I need to let go of? How can I model leadership? How can I bring people with me?”

As Bina M. Patel, our PLACES facilitator, so often reminds us, “Find your purpose”. We must remember it’s not just our work. If we die tomorrow, the work continues. We must create our own paths and persevere. As hard as it is to sometimes accept, even in times where you feel like you have no agency and are complicit in oppression—find your power. Know your power.

There was a time that I operated in hopelessness. This world can so often be calloused and cold. But I am learning that this is simply my trauma response. Community trauma is often cause by social inequities, oppression, erasure. But guess what? We deserve healing. We deserve joy. We deserve to win. And I can fight for that. I will fight for that. I’ll fight so that the trauma does not define me or our movements. This is where the true liberation comes in.

For me, that is the work. I choose to be healed.

Let’s find grounding so that we can:

1. Embody this work.

2. Create wins and avenues of joy.

3. Rise above.

I want to thank the Tribal Council and the Lakota peoples for humbly inviting us into their space at Standing Rock Reservation. What a unique and precious opportunity. Thank you for sharing your stories with us.

About The Author

Tonja Khabir is 2019 PLACES Fellow and executive director of the Griffith Family Foundation, a social entrepreneur and community relations specialist from Macon, Ga. She has managed and supported programming in the fields of public health, community development, and education for over 10 years. As a bio-behavioral health researcher, Khabir supported teams in East & Southern Africa, enhancing health and development in vulnerable communities with organizations like USAID, International Organization for Migration, Global Health Action, and the University of Western Cape. She returned to her hometown of Macon in 2014 as the founder of Two Hands International, a nonprofit encouraging global leadership for underrepresented high school students in Middle Georgia.

She is a 2018 Emerging Cities Champion with 8 80 Cities and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. She is a founding partner of Urbane: Young Black Professionals Network of Central Georgia and was named a 2018 Emerging Leader with NewTown Macon Partners in Progress. She serves on several boards and in Macon- Bibb including the United Way of Central Georgia, the Grand Opera House, and the ONE Macon Strategic Planning Committee. Tonja has a B.A. in Sociology from Fisk University and a Master of Public Health from Morehouse School of Medicine.

She loves yoga, reading, traveling, cooking and the arts.

Lead the way. Be the change. 2020 PLACES Fellowship Application Now Open!

By Martha Cecilia Ovadia, Senior Program Associate, Equity and Communications

This year marks the 10th anniversary of one of the Funders’ Network’s most significant efforts to foster leadership in philanthropy: the PLACES Fellowship. PLACES — which stands for Professionals Learning About Community, Equity and Smart Growth — has welcomed 127 fellows to participate in a yearlong learning opportunity to help grantmakers embed the values of racial, social and economic equity into their work. By the end of their fellowship, participants are equipped with the tools and resources to understand, challenge and change systemic inequities. Our alumni hail from all corners of the United States and Canada, representing national, regional and community foundations.

TFN is happy to announce that we are now accepting applications for the 2020 class of its PLACES Fellowship!

For more information on the PLACES Fellowship, click here.

Applications are due Nov. 1, 2019.

In Their Own Words: Fellows Share Their PLACES Stories

For the 10th anniversary of TFN's PLACES Fellowship, we worked with two award-winning journalists to help capture the stories shared and the lessons learned through the PLACES Fellowship. The result is our PLACES Impact Stories project, which includes profiles written by WLRN social justice reporter Nadege Green and videos created by documentary filmmaker Oscar Corral.

We've also continued our popular Going PLACES blog series, which features original content from our PLACES Fellows. Our gratitude to all of the PLACES Fellows alumni who have taken the time to share their own stories of impact with our network. We hope you find them as inspiring and illuminating as we do.

PLACES Impact Videos

We invite you to hear directly about the impact the PLACES fellowship has had on its fellows and their work in our PLACES Impact Videos. You can watch these videos, including this video from Susan Dobkins, Program Director for the Vista Hermosa Foundation and a PLACES 2012 Fellow, here.

PLACES Impact Stories

We asked PLACES alumni to share what inspires, motivates and challenges them in their efforts to embed the values of racial, social and economic equity into their work. You can read all of her profiles, including this one from Kris Archie, Executive Director of The Circle on Philanthropy and a PLACES 2016 Fellow here.

Going PLACES Blogs

After each PLACES site visit, we ask the fellows to reflect on their experiences in our blog series Going PLACES. Check out the many blogs written by our fellows on the ground here, including #StayWoke Philanthropy: Owning our role in the system, a reflection on a PLACES site visit to Miami by Mordecai Cargill of ThirdSpace Action Lab.

ABOUT PLACES

In 2008, the Funders' Network launched PLACES (Professionals Learning About Community, Equity and Smart Growth), its first philanthropic leadership development initiative. PLACES is designed as a year-long fellowship program that offers tools, knowledge and best practices to enhance funder grantmaking decisions in ways that are responsive to the needs and assets of low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Narrowing the Equity Gap Through Creative Placemaking

By Kresge Momentum (crosspost)

Rebecca Chan, program officer for economic development at LISC and 2018 PLACES fellow, was recently featured as part of the Kresge Foundation's Momentum project,

which explores the stories of eight leaders whose work is creating positive changing in American cities.

The series of stories brings to life the experiences of people

working in climate adaptation, higher education, public health, community investment and more.

Chan shared her belief in harnessing the power of the arts to bring people together.

"Chan grew up in Skokie, one of the most ethnically diverse cities in Illinois. It was there that she saw how participating in the arts helped make the community more cohesive.

'It was usually the arts that brought people together,' she says. 'It transcends languages and culture and other kinds of social boundaries. I always thought about (it), but it’s really kind of manifesting in what I’m doing now.'

It was a formative insight — as was hearing about family members who had been denied opportunities because of the color of their skin. As a person of mixed race, she also sometimes encountered bias.

Chan grew determined to confront those injustices. Today, she is an emerging leader in the field of Creative Placemaking, combining her appreciation for the arts with her passion for social justice."

Read the full piece here.

About the Author

Rebecca Chan is the program officer for economic development at LISC. She helps LISC partners across the country leverage arts, culture, and the creative economy to achieve community development outcomes. Before joining LISC in 2016, Rebecca was a fellow at Reinvestment Fund and served as a program officer for the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation. Rebecca was also Program Director for Baltimore’s Station North Arts & Entertainment District, where she worked with artists, residents, businesses, and anchor institutions to deploy a place-based revitalization strategy utilizing arts and culture as an organizing tool. Rebecca has been recognized as a Funders Network PLACES Fellow (2018), and a Fellow of the Salzburg Global Forum for Young Cultural Innovators (2015). She received her MS from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, and a BA from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Join Us For The Inclusive Economies 2019 Inaugural Meeting!

By Martha Ceciliai Ovadia, Senior Program Associate, Equity and Communications

Registration Now Closed

Due to the high level of interest in the inaugural meeting of TFN's Inclusive Economies, we have reached capacity for this meeting.

Inclusive Economies will host it's inaugural meeting November 4-6, 2019 in Cleveland, Ohio.

TFN's Inclusive Economies focuses on race, place, and power-building and is open to all national and place-based funders

___________________________

| About Inclusive Economies Even as income inequality and the economic effects of racism are elevated to the center of national debate, the job of addressing economic inequity continues to fall largely to local leaders. For funders, this raises a host of strategic challenges. What role can philanthropy play in mobilizing local assets to expand and extend opportunity to marginalized communities? How can funders ensure that economic growth translates into economic opportunity and access? And how does philanthropy help build local capacity and power to confront structural racism that has prevented people and communities of color from prospering? We’ll tackle these questions and more at the first annual meeting of TFN’s Inclusive Economies working group in Cleveland, Ohio. This inaugural convening provides a dedicated forum for place-based funders invested in economic equity to meet and learn from peers, thought leaders, and local residents; share work in progress; and build a common agenda for learning and action. Join Us In Cleveland Join your funder peers as we launch this new line of work dedicated to race, place and power-building for shared and restorative prosperity. In addition to topical sessions on critical issues like neighborhood displacement prevention, the future of work, and good jobs, the program includes ample time for peer exchange, small-group discussions, and socializing. Click here for working agenda. Highlights: |

| Book Your Room: Please make sure you've reserved your hotel room. Our TFN room block at the Hilton Tru is now sold out as well, so we would also like to suggest the following nearby hotels for those who still need to make reservations: The Tudor Arms Hotel Cleveland, 10660 Carnegie Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106, 216.455.1260 Residence Inn by Marriott Cleveland University Circle/Medical Center, 1914 E 101st St, Cleveland, OH 44106, 216.249.9090 Holiday Inn Cleveland Clinic, 8650 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106, 216.707.4200 |

Going PLACES: A Moment In Your Day

By Michelle Morris, Director of Community Philanthropy, Duluth Superior Area Community Foundation

Take a moment from the demands of your beckoning calendar to consider this with me:

Visualize yourself with your family and friends enjoying the places you feel most connected with and doing the things that make you happy and fulfilled. Pause while the sights, sounds and smells bring you a sense of calm and you might even be smiling a little.

Now imagine that this place is no longer yours. You cannot be here anymore. You, your family and your friends can no longer do those activities that brought you joy. Imagine that having lost what makes you feel complete, you courageously raise your voice to express that this is not right and draw attention to it. Not only are you not heard, you are spoken over by a louder voice using words that are distorting what you are saying.

“That could never happen,” you might be thinking; or you might be feeling sorrow, fear and anger at the thought of this; or maybe this has happened to you, your family, and your friends. The Dakota men, women and children of the Standing Rock Tribe have had spaces and traditions that are deeply a part of who they are taken and threatened. They continue to be spoken over and experience the pain of violence. This is reality. This is today.

Many people heard about the Standing Rock “protests” in the news, and perhaps you shared these stories, too. Think back. Where did you hear and read these stories? Who was telling them? As you consider this, are Dakota tribal members coming to mind as prominently as the journalists and activists? Very likely — no. As you consider losing what you care most deeply about, imagine your outrage at this violation: Not only are you not heard, the reality of your experience is being invalidated and erased.

I am challenging myself and you, particularly if you have white skin like I do, to amplify the voices of people of color telling their own stories. “Our people need to tell our story,” I heard a Standing Rock tribal member say at the PLACES Fellowship’s place-based learning experience.

What many people do not know is that the Standing Rock situation began as prayers by community members. Their prayers were co-opted by primarily white activists and were distorted into violent protests. The damage continues to affect members of Standing Rock, and not for the first time. While visiting a memorial for Chief Tatanka Iyotake — Sitting Bull — it struck me how similar the present is to the past. The memorial reads:

“Tatanka Iytake was killed by Tribal police at his home near Grand River on December 15, 1890. Tribal police were acting on orders to bring him into the agency in order to quell the Ghost Dance [a ceremonial dance they believed would bring back the old ways of life].”

Silencing by dominating the narrative and perpetrating violence against Native Americans continues today.

In addition to stories, consider another of our dominate ways of knowing, often more accepted as truth and upon which big decisions are made: Data. Numbers. Quantified measures. When you have finished reading this post, look up the demographic data that informs your own and your organization’s decision-making. Take note to see if Native Americans are included or if this entire group of people(s) have been excluded from the report, perhaps because of low numbers or because the data is aggregated across tribes making is less locally relevant. This is vital information when we apply it to philanthropic efforts for educational access and economic opportunity. We must support Native American communities collecting their own data to tell their own stories.

Along with the influence of stories, consider the influence of our dollars, both personally and professionally, and how they flow through our communities. Which businesses owned and operated by people of color do you utilize? One extraordinary business leader I met during this experience is Holly Doll, President, president of Native Artists United. The mission of Native Artists United is to support “the livelihood of Native artists by advocating for presence and opportunities to gift knowledge and skills, build capacity, and showcase Native art.” Consider how you can identify more businesses owned and operated by people of color and include them in your routines — see how your philanthropic dollars can also support developing entrepreneurs of color in your community. This flow of money is vital to the financial stability of communities of color.

A quote from Chief Tatanka Iyotake written on his memorial continues to come to my mind after this site visit that needs honest recognition and reparation still today: “What treaty have the Lakota made with the white man that we have broken? Not one. What treaty have the white men ever made with us that they ever kept? Not one.”

It is now a federal felony to protest pipelines. This does not align with Tribes being able to assert their sovereignty. As white citizens of the Unites States, we must participate in this democracy and hold our government accountable. As one tribal member said, “Treaties are the supreme law of the land. When the United States upholds them, then we can address social determinants of health and economic development.” Recovering from traumas will require going back to tribal ways and traditional culture and spirituality. Restoring connections with culture and the land is vital to the Standing Rock community.

There are two values I want to share that I brought home from the Dakota and Anishinaabeg cultures that I believe, if we all practiced them each day, would create drastic change:

1. Rather than say “that was powerful”, speak and act upon “that made me feel humbled.”

2. We must lead our lives for the world seven generations to come.

One last time, take a moment with me to consider the values that matter to you personally and those of your organization. How have you acted upon them already today? How will you include them in your time to come?

About The Author

Michelle Morris is Director of Community Philanthropy at the Duluth Superior Area Community Foundation. She advances the Foundation’s mission of private giving for the public good by partnering with nonprofit organizations and community leaders throughout northeast Minnesota and northwest Wisconsin to create positive outcomes through grants and scholarships. In addition, Michelle coordinates grantmaking for three initiatives: 1. Closing the opportunity gap by building a community that embraces diversity and inclusivity, where all children have abundant opportunities, and feel respected, safe and secure; 2. Increasing communities’ abilities to prepare for, respond to and recover from disasters, while particularly focusing on the community members who are most vulnerable; 3. Attracting and retaining young adults in the region through civic engagement, entrepreneurship and high quality of life.

Michelle earned her Master’s in Public Health from Columbia University, focusing on social determinants of health and health equity within health promotion. Michelle brings to her role experience in program design and management, evaluation through qualitative and quantitative research methods, community-based participatory research, and grant proposal writing and review.

No Time for Complacency

By Mariella Puerto, Co-Director of Climate, Barr Foundation

Mariella Puerto, co-director of Climate at the Barr Foundation and co-chair of the Funders' Network's GREEN! working group, recently wrote a post for the foundation's blog . The piece was timed to coincide with the release of The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) rankings of 75 large US cities for their work on energy efficiency, clean energy, and reducing emissions.

"New scorecard celebrates U.S. cities leading on clean energy. Yet, even leaders must do more to access the full economic opportunities and to address our climate emergency.

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) recently released its newest ranking of 75 large US cities for their work on energy efficiency, clean energy, and reducing emissions. In this fourth edition of the City Clean Energy Scorecard, Boston retained its #1 ranking, followed closely by San Francisco, Seattle, Minneapolis, and Washington. Given impressive strides and strong momentum, Cincinnati, Hartford, and Providence gained special notice as “cities to watch."

It is encouraging to see so many cities engaged in this critical work, and even competing to outdo one another. As ACEEE stressed, however, all cities “have considerable room for improvement, even those ranked in the top tier.” This is no time to be complacent. The harmful effects of climate change are accelerating and growing more severe every year. As United Nations secretary general António Guterres pointed out in his March 2019 Op-Ed in the Guardian, “climate delay is almost as dangerous as climate denial.” If we fail to move quickly and boldly enough, we will be too late to make a difference. We also risk missing out on a massive opportunity to create good-paying jobs and spur just and inclusive economic development. Although the United States is among leading nations in renewable energy growth, other countries started sooner, are investing more, and are moving faster than we are. We can still catch up, compete, and even lead. Yet, without greater ambition and more visionary policies, we risk being merely bit players in the world’s next major energy economy."

Read the full piece in here.

About the Author

Mariella Puerto is a co-director for Climate, managing Barr’s grantmaking and other initiatives that catalyze the transition to a clean-energy economy. This includes promoting policies and practices that accelerate the adoption of energy efficiency and renewable power sources in the New England region and connecting to similar efforts nationally. She serves on the board of the Environmental Grantmakers Association and as co-chair of the Funders’ Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities’ GREEN! Working Group.

Going PLACES: What the Newark Rebellion can teach us about Philanthropy

By Grace Chung, PLACES Fellow and Senior Community Development Officer, LISC New York City

Going PLACES is an occasional blog series featuring the voices and experiences of TFN’s PLACES Fellows. For more information on the fellowship, and to read past blog posts from our fellows, visit here.

When I got off the PATH station at Harrison, a suburb of Newark, I arrived in an almost unrecognizable neighborhood. Everything seemed to be either under construction or built in the last five years, including a new PATH station, multiple gated luxury housing complexes, and an artisan “boutique” coffee shop.

I had gone to college near Newark and returned almost a decade later through the PLACES Fellowship, which teaches people in philanthropy how to incorporate racial equity into their work through the lens of four site visits around the country. As we drove through downtown Newark, I learned that changes weren’t limited to the city’s periphery. New companies had moved in—like Panasonic, Whole Foods, and Audible—and existing companies like Prudential had expanded, bringing new jobs with it. Housing construction was booming, along with a restaurant scene, which attracted celebrity chefs like Marcus Samuelsson.

The physical transformation of Newark is striking, but as I learned during the three-day PLACES visit, the rising tide of economic growth has not benefited residents evenly. Far from it. In a panel about workforce and economic development, local experts rattled off the daunting statistics: the average income is $34,000 and poverty rate is still above the national average. There are more jobs, but Newark residents hold only about 18% of them (far lower than other major cities) and limited affordable homeownership options continue to be a barrier to wealth building. Only about 22% of Newark residents are homeowners—which one speaker pointed out is about the same as in the 1960s. The rest of Newark residents are renters, who are increasingly feeling pressure as rents have risen over the past decade.

In another panel on arts and culture, we learned that “the arts is selling Newark” to real estate developers and newcomers (and was even a carrot featured in Newark’s video to attract Amazon’s HQ2). But at the same time, long-time local artists are finding it harder to remain in place. Just recently two black-owned art galleries closed down. Unable to afford local rent, nonprofits like Newark Arts, have turned to cajoling private developers to try to offer up space to house local art. When a fellow asked local poet, Khalil Murrel, if he plans to stay in Newark, he half-joked that he will stay, so long as he can afford the rent.

One explanation for persistent poverty in the face of Newark’s economic growth that many still come back to is “the riots”—referring to five days of unrest between residents and police in 1967 which left 26 dead and hundreds injured. The Newark-born writer and economist Richard Florida describes the “riots” as a turning point, which signaled the start of an “urban crisis” in which “middle-class people and jobs were fleeing cities like Newark for the suburbs, leaving their economies hollowed out.” White people and their companies left, and those that stayed found ways to isolate themselves through fortress architecture exemplified in the Gateway Center (which one of my fellow PLACES colleagues explained, uses elevated “skyway” tunnels to connect office workers to the train station so that they wouldn’t have to interact with people on the streets.)

A visit with the electric, white haired Junius Williams, nicknamed “the historian of Newark” by the Mayor, provided more to the complex story. “If one has to push the foot off their neck, that’s a rebellion, not a riot,” said Williams who was a law student at the time. Now an educator at Rutgers University, Williams developed a website which he showed us called RiseUpNewark which pieces together oral history and photos which bring Newark history to life. It shows that well before 1967, the relationship between (majority white) police and black community were tense because of repeated incidents of police violence. And even before the so-called “urban crisis”, white families (like Richard Florida’s) were already leaving Newark because they could. As factories closed, white families with access to loans through the GI bill moved freely to suburbs to buy homes without discrimination. Meanwhile, essentially all of Newark was redlined - referring to a federally sanctioned practice in which lenders would draw red lines around communities deemed too “risky” for loans because of the high concentration of people of color.

This historic context illuminates that the events of 1967 did not “just happen” over a few days but were catalyzed by decades of policies and practices. What is equally important though, Williams is quick to point out, is what happened after the rebellion. As white people abandoned the city, Williams and hundreds of others took to work in community organizing and rebuilding what was left. Reflecting on that time, some of his proudest memories of Newark include organizing alongside neighbors for new affordable housing, establishing a workforce program, and in 1970, taking on the Democratic party to elect Newark’s first black mayor through an entirely grassroots campaign. Early on, neighbors and local churches pitched in resources to support these movements, artists re-opened abandoned spaces, and later in the 1980s, LISC Newark—a nonprofit community development financial institution (CDFI)—was opened, going on to finance thousands of units of affordable housing and community spaces. After years of disempowerment, first by slavery, then by racist policies and practices, black Newark residents were shaping their future.

In 2017, the New York Times approvingly declared “New Jersey’s largest city is finally turning a corner”, transforming into a “hub for the arts and higher education and the growing vibrancy of its bustling ethnic neighborhoods”. The revitalization has not gone unnoticed by the real estate industry and large corporations. Now the question is, will long-time Newark residents get to stay and benefit? There is reason to be hopeful. Newark residents have taken pre-emptive measures to secure protections such as tightening rent control laws, inclusionary zoning which requires a 20-30% affordable housing set aside for new housing construction, and most recently, right to counsel legislation. But these movements will need sustained support in order for Newark’s growth to be shared equitably.

In PLACES, we learn that powerful questions are essential to disrupt that status quo of whiteness that perpetuates the professional world—including in philanthropy—and move us toward racial equity. These are two that emerged from my visit to Newark, which have stuck with me:

- Instead of asking, “What is lacking in communities of color?” we must constantly be asking, ‘what are the systemic and historic reasons that have led to racial disparities?”

- Instead of asking, “How can we help communities of color?” we must ask, “how do we direct more resources to communities so that they can be at the center of creating their own solutions?”

My visit to Newark left me with the conviction that—now more than ever before—it is necessary for philanthropy to support residents so that they can continue to have a voice in determining their own future. For Judith Thompson Morris, one way that LISC Newark is doing this is through the Newark Resident Leadership Academy, which provides leadership training for residents and small grants to implement neighborhood-driven initiatives, and in the process build up local networks. For Williams, what is most essential is supporting the grassroots organizing which rebuilt Newark in the first place. Both Morris and Williams agree: charity will not help Newark; only sustained support for community led initiatives will bring about long-term systemic change.

As Williams told me after our visit, “If donors want to see change in America, they have to be willing to invest in the people who are willing to bring about that change—people willing to take risks, to take a stand and make sure others come to understand that they too have the power to make change.”

About the Author

Grace Chung is the Senior Community Development Officer for LISC New York City. She is a current fellow in the 2019 PLACES class.

Going PLACES: The tools we use and the truths we seek

By Dominic Braham, PLACES Fellow and Assistant Program Officer for LISC Phoenix

Going PLACES is an occasional blog series featuring the voices and experiences of TFN's PLACES Fellows. For more information on the fellowship, and to read past blog posts from our fellows, visit here.

The inequities in workplace, community development and philanthropy are very real to many, including myself as a cisgendered African American male in the space of nonprofit community development work. These organizations exist to empower and fund projects that mainly impact people of color, but the majority of internal leadership does not reflect those demographics. Imagine you are a person in a leadership position where the outcomes of inequity such as redlining, slum lords, predatory lending, lack of business investments and systemic racism affected your family or even your personal life while doing this work. Now picture someone in a leadership position, who does not have to experience the outcomes of inequity personally and then the only incentive for them to do the work is “caring” about the work. Which person do you think will understand the need to push for systems change and be more impelled to take risks in improving the lives of others?

I feel fortunate to have found this fellowship of Professionals Learning About Community Equity and Smart Growth (PLACES) with the Funders' Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities. There is a disproportionate impact that happens when excluding the perspectives of low-income communities, often comprised of people of color, from decision-making about growth and development in their communities. The PLACES Fellowship provides the tools and resources to help those working in philanthropy to understand and eliminate the impact of these decisions.

Our first site visit to Newark helped me verbalize and strategically think about how to navigate racial equity at individual, communal, institutional and structural levels. I was able to reflect on my own privileges, such as speaking a second language, growing up with both parents, owning my own home and having fairly good health. Some of these privileges were inherited and some were attained based on my own actions. Acknowledging these privileges in my work can make me more aware of and sensitive to that bias between staff and the communities we serve. A simple example is the centering of whiteness for featured panel speakers on topics that affect low income communities of color. The lack of panel speakers who represent the community can feel almost offensive when we are talking about issues that affect that community. Continuing to center whiteness as thought leaders and featured panelists limits the conversations to a “white savior” model.

After attending our first PLACES site visit I am now asking myself:

"Am I perpetuating or pushing the status quo in my work?"

"Do I accept responses from decision makers in leadership regarding interest in funding minority-led organizations such as, 'Well, you know this will be a heavy lift', 'they just don’t have their accounting in order for us to give them a grant', 'we tried this before and it did not work', and 'that organization is just not ready yet'? "

" Do we, as leaders, choose silence? "

These questions are valid, but they may not bring about the system changes we desire. The practice part of racial equity involves asking powerful follow-up questions that challenge these archaic operating procedures that perpetuate inequity and exclusion. Following up with a truth-asking practice such as, "What structures of power and privilege are we upholding with these procedures that exclude certain organizations?" is the practice of doing racial equity.

Based on our first site visit and our learning there, here are some tools to advancing racial equity that I am currently working with:

- A “redesign of our mindset” to address our own biases.

- Consistent, incremental action is transformative. Find the next immediate step – include someone new in the conversations, ask new questions, use different language. Practice.

- Decolonize the “this is how we always have done it” mentality.

- Identify, acknowledge, and redesign points at which exclusion, hierarchy, withholding, power asymmetry, are perpetuated.

I have a few personal takeaways from our trip to Newark and from my own work experiences I'd like to close with. One comes from Newark historian Junius William, who at one of our panels stated, “The power of 'who controls the narrative' is vital.” There is so much more to American history than what is taught in schools. A specific example that comes to mind is Benjamin Banneker, the African American inventor of crop irrigation systems. During the revolutionary war, wheat grown on a farm designed by Banneker prevented U.S. troops from starving. There is also Garrett Augustus Morgan who invented an early traffic signal, which greatly improved safety on America's streets and roadways.

Along with the African American narrative, I have also been thinking about my own personal narrative - the stark difference of how we are seen and regarded in the eyes of our own professional/personal connections in our community compared to how we are looked at inside our own organizations and communities. I often speak with many young African Americans in community development who share the feeling of their work and worth being questioned within their organizations. Can you imagine the impact of having the support and influence of connecting resources to the social networks we hold with deeply rooted members of community, without any exclusionary red tape?

My vision for systems change is twofold. The first is changing the paradigm of how our philanthropic and community development organizations recruit and foster talent. We must allow those who come from communities that are affected to hold power in leadership efforts for their neighborhoods. We must not look at having strong individuals on our team as a threat to leadership, but allow staff to flourish in their strengths. The second would be a shift in decolonizing the internal “this is how we always have done it” mentality at our organizations Leaders must create a space were we can bring awareness and call out our unconscious bias in how we go about the work. If these changes can happen internally, I am certain the impact in dis-invested communities will be improved.

I know we are on the brink of this shift and many organizations currently are making these changes. Let’s keep the momentum going!

About the Author

Dominic Braham is an Assistant Program Officer for LISC Phoenix. He is a current fellow in the 2019 PLACES class.