By Sara McCarthy is Director of Communications at the Fund for Our Economic Future

The work of TFN’s new Inclusive Economies working group began in earnest with the group’s November 2019 inaugural annual meeting in Cleveland. This is the third in a series of guest-authored posts that reflect on key meeting sessions and topics. (Click to see the meeting agenda and read speaker bios.)

Entangled with concerns about automation and job scarcity, few topics elicit more debate than “the future of work.” For Inclusive Economies’ panel on the topic, TFN asked Heidi Shierholz, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C., to lay the groundwork for an evidence-informed discussion of the trends shaping the future employment environment, and their implications for marginalized workers. Shierholz’s remarks prompted spirited exchange among fellow panelists, who brought a wealth of policy, research, workforce, capital deployment, advocacy, and power-building expertise to bear on the question of what it will take to create well-paid, high-quality work for all. Here, Sara McCarthy of the Fund for Our Economic Future shares the top-line takeaways from the discussion.

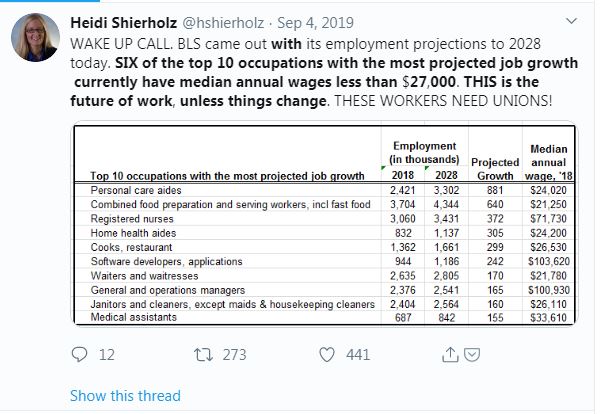

This tweet, originally posted after the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its 10-year employment projections last September, neatly encapsulated economist Heidi Shierholz’s central message to the funders gathered to hear from her and other panelists during their session at the Inclusive Economies inaugural meeting. Contrary to fears, the biggest threat to working people is not that automation and artificial intelligence will reduce the overall number of available jobs. Throughout history, jobs lost to technological change have been offset by the rise of new jobs. Rather, Shierholz says, the real threat to workers, especially to women and people of color, is that so many of the jobs available in the future will pay so little.

This assessment set the stage for a lively and occasionally heated discussion of how this national trend is playing out now in local communities. Panelists’ concerns included the validity of the employment data and the effects of automation on individual people; the push for entrepreneurship versus employment (and the detriments of that); the relationship between employer and employee; and the barriers that exist to quality work.

A consistently unifying theme was the centrality of race in workforce discussions. As panelist Caryn York, CEO of Job Opportunities Task Force in Baltimore, asserted, “The workforce is not monolithic. Race and place have to be front and center when we deal with these challenges.”

Another point of agreement: Programmatic responses won’t be enough to reverse decades of declining wages and erosion of worker supports. Meaningful change in the workforce arena will require policy change.

For Shierholz, this means a multi-pronged approach to ensure worker well-being, including a stronger safety net and a good jobs agenda based around support of unionization, increasing the minimum wage, and paid time off, as well as strong enforcement of these policies.

Where does philanthropy fit in? The panelists offered several concrete suggestions during the session, moderated by Emily Garr Pacetti, vice president and community affairs officer for the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Fund research. This is hugely important when it comes to policy work, York said. Panelist Carmen Rojas, founder of The Workers Lab in Oakland, Calif. (and incoming president and CEO of the Marguerite Casey Foundation), added that funders often shy away from policy work that has a value statement attached to it. There is confusion that this is inherently partisan, she said. “And it’s not. As funders in this space, we need to keep pushing.”

Trust more. “We see capital markets consistently fail low-income communities and communities of color,” said Michael Jeans, president of Growth Opportunity Partners in Cleveland, who also participated on the panel. “Let’s create mechanisms where we aren’t telling people we trust them, we simply trust them. … Are we giving the capital to the people who look like these communities and people who care about these communities?”

Reframe the narrative on working people. “Is the support of entrepreneurship by philanthropy contributing to the dilution of worker power?” one audience member asked. “We have all kinds of jobs. We need to make sure those jobs are good,” Rojas said. “We look down on working people in this country. That is so damaging. We need to make the distinction between employment and entrepreneurship, and make the distinction about what we want from those.”

About the Author

Sara McCarthy is Director of Communications at the Fund for Our Economic Future, where she leads the Fund’s awareness building efforts, overseeing the strategic communications of a wide variety of Fund initiatives, including The Two Tomorrows, The Paradox Prize and job hubs. Sara grew up in Warren, Ohio, and is proud to be a part of its manufacturing heritage, having worked at a now-shuttered steel mill while pursuing a bachelor’s degree from John Carroll University. Sara spent several years as a business journalist, first in Cleveland then in New York, before earning a master’s degree in public service at DePaul University in Chicago. She spent a short time slinging pies at a bakery before returning to Northeast Ohio to work for the Fund for Our Economic Future.

More in this Series

You can read additional takeaways from the inaugural Inclusive Economies meeting in this blog post series:

Treye Johnson of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland: “Inclusive Economies: Awareness building to more thoughtful action.”

Cari Morales, National Urban Fellow at the Cleveland Foundation: Inclusive Economies: Investment, displacement & engagement